Thursday 28th September 2023

Hosted by David Cran and Mark Crichard

In our final roundtable of 2023, two of the UK’s leading technology lawyers David Cran and Mark Crichard of RPC bring a new perspective to attendees’ technology issues. In their session on how to Contract for Success, they covered how to set up projects for success, the contracting pitfalls to avoid, and effective management of distressed projects.

70% of transformation projects fail, bringing costly legal disputes to organisations, which Chief Architects are often drawn into. Utilising their extensive practical experience, this blog highlights the key legal and strategic points raised by David and Mark in the session.

David specialises in technology disputes and provides his thoughts on when projects go wrong, with Mark providing his valuable insight into the negotiation and contracting of technology transactions – his day-to-day bread and butter which includes technology, telecoms and all forms of outsourcing transactions.

Suppliers are well-positioned to manage tender processes because they are doing this for a number of customers. This means their escalation routes and teams are more constant. Customers, on the other hand, are usually setting up a new contract and consequently are dealing with new people and a new process.

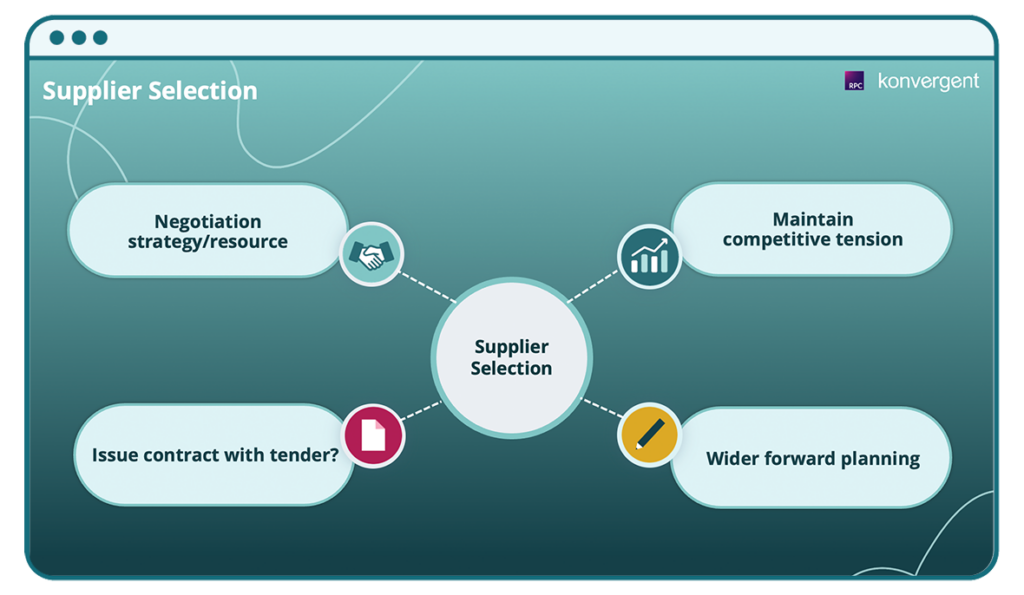

This often gives the supplier greater negotiation power – a key theme emphasised throughout David and Mark’s presentation. To wrestle this back, understand your escalation points, how to raise queries/issues, and who to raise them with. Instead of leaving the difficult part of negotiations to the end (it is only natural to want to park more challenging decisions), draw these decisions into an earlier part of the negotiation to avoid an unwanted but natural consequence – customers naturally tend to concede more towards the end of contract negotiations. It can be tough, as most projects will require lots of resources, time, and money, but maintaining competitive tension by inviting two or three suppliers to bid (and negotiating with more than one of them) can really pay off.

Another way to protect your position is by fully capturing everything you agree with your suppliers as you go along. Negotiating parties often mistakenly think a point has been agreed upon, when in reality they haven’t. In Mark’s experience, some suppliers may have a tendency to backtrack and it is especially important to capture details during the early stages of negotiations (and it’s so easy to do this digitally).

Other key strategies for customers are: first, think carefully about going out to tender with a proposed draft contract (for bidders to comment on as part of the tender). Secondly, focus on operational elements right back at the planning stage. Leaving small, but important details such as acceptance processes until later can diminish your negotiating power resulting in arrangements skewed towards the supplier or just ill-thought through.

Use the negotiating process to find the Supplier’s “pinch points” by asking them to comment on descriptions of terms, pricing, terms & conditions, so that you can see what will cause a problem for them. Finding those problem areas before you sign the contract isn’t necessarily a bad thing, while a supplier who just says yes to everything might be.

The negotiations give you a chance get to know the character of the supplier, often best done in face-to-face meetings, rather than via Microsoft Teams. When the end of a tender process approaches, you really can learn a lot about them as difficult conversations are needed. Often that character will then carry into the project itself.

Contracts should tell a story (that’s why basing the contract firmly on the facts of the situation is so important). Mark highlighted a piece of work he did for a company in the 1990s, where the MD of the firm understood everything clearly as the contract told the story. A sound contract is not just made up of legalities but allows readers to understand in simple terms how the agreement (and the project it relates to) works. Mark mentioned that the trend for more complexity, or “clause inflation”, risks creating more confusion. The contract is meant to be a living document – a roadmap that you can go back to, and not a bottom drawer filler.

A contract should contain essential “legal” terms, such as force majeure, limits of liabilities etc but it’s also crucial for them to include a technical description of what it is you are buying, a detailed specification of works, milestones and key dependencies.

Escrow is a legal arrangement in which a third party temporarily holds money or property until a particular condition has been met (such as the fulfillment of a purchase agreement). Whilst this may not always be an appropriate option, it remains important to consider how you would deal with things going wrong. For example, there can be an unwanted ripple effect when a subcontractor or supplier fails to fulfil their obligations. What happens if your supplier has failed to pay the cloud provider? Will you be able to get into it and retrieve your credentials? Here, escrow acts as a safety net.

Mark’s responses to some thought-provoking questions:

A: Finding them early gives you a better chance of understanding the upside of the supplier. It will give you the opportunity to assess and understand their thinking process. It is possible to tease this out of them, it’s not rocket science, but just requires you to tactically draw it out of them.

A: Have people read the contract terms, and understood them? Suppliers will look to make as few amendments as they can (showing “less red pen”) in a tender, but will seek changes that can have big impacts in terms of the contract. One example Mark provides concerned an outsourcing provider working with banks, using long, complex agreements. Mark inserted a line within the contract for his client that stated that their line of work is very much people based, and that people are prone to making errors, so the outsourcer could not always guarantee 100% accurate work all of the time (ie attempting to rule out liability for a single “fat finger” error). A fair term on the face of it, but one that could have huge impacts if things go wrong. In situations like these there needs to be a meeting of minds on what projects should encompass.

A: Unfortunately, some lawyers tend to be nervous about agile methodology as they prefer certainty, detail, a defined outcome and, where possible, a fixed price. Agile can work for some types of projects, and with certain customers and suppliers who are used to working this way — you can try fast and fail fast if required.

An example, drawn on by Mark and David involved an agile project that didn’t have a suitable change control process. Agile was within the framework specification, which kept changing, but which could only be formalised through a slow and cumbersome change process (which could not keep up with the agile timescales). The resulting contract operated as a waterfall contract, but for an agile project. This customer liked agile, but also liked the certainty of a fixed price and tight change process. By the time they were 6-8 sprints in, the gap between IT operations and the contract could not be closed.

A: Financial consequences can be leveraged (whether that is through milestone payments or service credits for failing to meet service levels), as most organisations will have financial consequences for late delivery or other key failures. It’s not usually huge sums, but it isn’t uncommon. Another professional anecdote from Mark concerned an airline who were in the process of changing their crew management system. Should the system not be operational, crew could not be allocated to flights and the airline might be forced to cancel them. Given EU rules requiring customers to be compensated for cancelled flights it was essential that suitable financial penalties around implementation and service delivery were included in the contract, to help to ensure that those obligations are be met.

The second half of the roundtable presentation was given by David, drawing from his expertise in tech disputes. With the focus on litigation, he joked that no one should really want to see him, and definitely should not be seeing him twice!

The red flags pictured left can provide an early indication of an incoming dispute.

David observed that when projects go wrong in the very early stages, they often tend to do so in a relatively minor way meaning a fix can usually be achieved. Two or three months down the line, real problems can emerge, and six plus months on, you’re potentially in deep trouble.

Some clients have shared that they do not want to go down the legal route, but the contract is there for that reason. Avoiding a difficult conversation is no reason not to raise a dispute. In most cases, David explains that the project team can continue working even if a legal process is happening in the background, so a dispute should not bring the project to a halt. Lawyers are there to prepare and position for you, should things need to escalate to court proceedings or to dispute resolution negotiations pre proceedings.

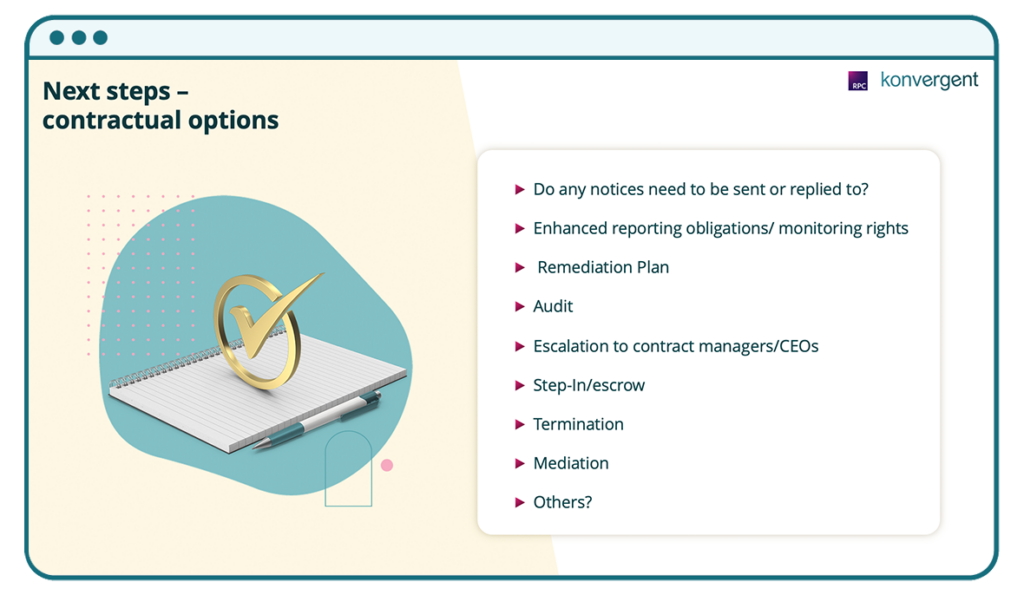

David highlights that customers should aim for a request for proposal (RFP) or other competitive bidding process, as this can make the selection process smoother and more efficient and mitigate costs in the longer term. Formal notices (ie drafted in accordance with the provisions of the notice or communication clause in the contract) should be utilised from the start – this manages expectations. He often sees scenarios where you have disputes and then notices start to rain down on the customer. But if the notice requirements, provided for in the contract, are followed, both sides benefit from certainty of process and know where they stand.

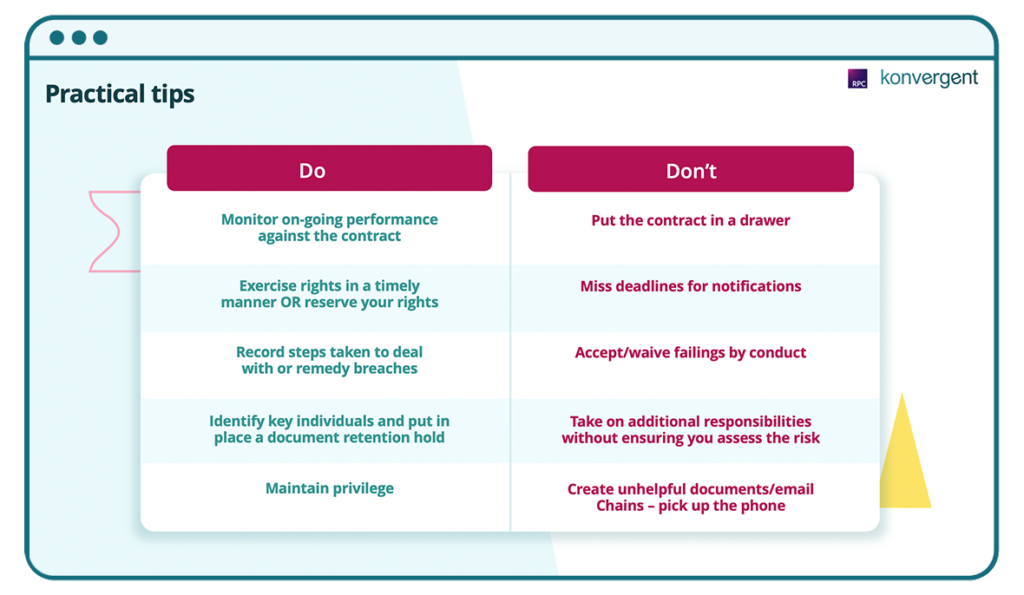

When managing the operation of, or changes to, the contract, if you are starting to find problems, document them, rather than wait until a dispute is underway. You want to be able to have a frank and open conversation with your supplier, so that an outcome can be agreed. If a dispute does come to fruition, you should have a clear idea of what you want to achieve from it. Have key objectives in mind, as a number of complex scenarios might arise from the legal, financial and commercial drivers linked to the dispute.

Termination is usually the nuclear option, yet David is seeing this becoming more common, perhaps because of the need to show the projects are delivering real value and some of the practical issues of migration are being addressed (eg through cloud services). Tech disputes are unusual beasts as they have such big operational consequences. Every contract will have a termination clause, but should termination occur, what do you next practically? Termination might appear to be straightforward on the legal side (it’s often not), but what happens on Day 1 after termination when your operation has come to a standstill?

Early in the negotiations, you should formulate an idea of what an exit plan may look like. Often this gets delayed or forgotten as everyone becomes exhausted with the process, but David and Mark have seen situations arise where some organisations go on for years without an exit plan, preventing or limiting termination as an effective option.

This is often seen within the construction industry, where projects are able to keep moving as actions are taken quickly to provide certainty (eg through an adjudication) – even if it’s rough justice, as David calls it. The tech sector has failed to adopt a similar approach. Disputes should not take over your project, as it is possible to provide for early resolution in your contract should it be required.

Finally, David states that you should plan for all key documents to be kept securely and readily accessible and for the key individuals to be identified. This will save time and effort should disputes arise, as you’ll be inundated with documents, and you need to know where the key documents are and who you need to speak to. All relevant documents also need to be preserved, as required by relevant court rules.

David and Mark emphasise – documenting everything is key, so that disputes can be identified and if possible resolved early to minimise disruption. Maintaining negotiating power is crucial as it affects the terms, enforcement, risk allocation and overall outcome of the contract. Parties with stronger negotiating power are often in a better position to protect their interests and achieve their objectives in complex and high-stakes agreements.

To keep the discussion going with David or Mark, please connect with them on LinkedIn here:

The 10th in the series of the Sessions with Konvergent roundtable events...

Integrated agile and governance is when multi-disciplinary teams apply agile approaches...

An Architecture tool is considered an essential part of an...

Poorly conceived visualisation can distract your audience from your core messaging...

Here is a selection of the most pertinent and interesting reads for Chief Architects this month, alongside our thoughts.

Konvergent,

The Hoxton, 70 Colombo St,

London,

SE1 8DP

T: +44 (0)20 3744 1256

E: info@konvergent.co.uk

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |